Briefings

The Pirc Family and their Dye-Works

THE MEMORIAL ROOM AT THE PIRC FAMILY HOME

Years ago, while tidying up and cleaning the home where our family has lived for over 250 years, I found numerous personal objects and memories – a legacy of generations past. Because each of these objects uniquely testifies to the life, work, and efforts of our ancestors, I value and respect them. They are part of a cultural heritage that has always been very important to us Slovenes and, with Slovenia's membership in the European Union, the importance of this mission has only increased

It is my conviction that this legacy is inseparably connected with our home, giving it special charm. I therefore decided to convert one of the rooms of the former dye-works, the mangle room (Slovenian monga), into a memorial room where my collection could be displayed.

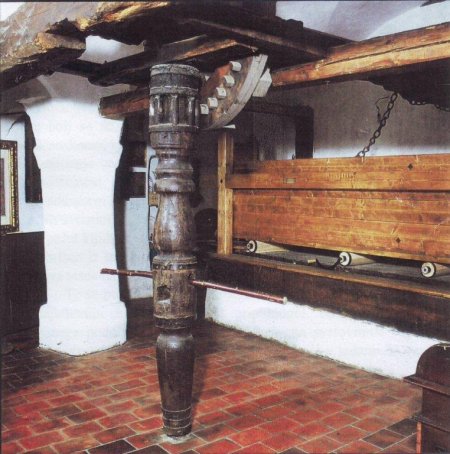

The monga: a device for ironing fabric (Photo: D. Holynski)

Even the room itself is interesting. It contains two ironing devices from 1797 and 1809. These are left over from the dye-works that provided food and income for seven generations of the Pirc family, and are rare preserved examples of mangles in Slovenia. A short description has been added to them, explaining about what it was like to work at the dye-works and how my ancestors combined dyeing with linen production, which enabled them to open up a shop in town. They consistently distanced themselves from the tradesmen's class and moved towards the middle class, which they felt closer to because of their involvement in raising national consciousness (promoting the rights of the Slovene nation and language), politics (Slovene autonomy in Austria-Hungary), their business activity, and their lifestyle. They held to the values of the middle class – values that led to progress and left their imprint, despite the fact that later this very class was long disregarded and erased from consciousness. A decisive factor for my ancestors was their close attachment to Kranj and the love that they had for the town.

This is especially true of my grandfather, Ciril Pirc. During the fifteen years that he was the mayor of Kranj between the two world wars, he helped it develop from a sleepy country town into the second most important town for the textile industry in Slovenia at that time. This is why he is given a special place in my memorial room.

I have already mentioned that the dye-works was closely connected with linen manufacturing, and this is why the room includes a short presentation of flax harvesting and processing in Slovenia.

The room also includes remnants of old middle-class items of clothing, objects that nostalgically recall reading clubs and genealogies, and documents about the development of the dye-works and the shop, and also about the development of cultural, sports, and economic activities in Kranj.

This museum came together slowly and gradually. It covers a number of different fields, and so it was necessary to find appropriate experts for each of them.

The cooperation with the Museum of Upper Carniola was the most fruitful and extensive; mention should be made of the late curator Nada Holynski, who was the first to encourage me, and Tatjana Dolžan-Eržen, who selflessly helped complete the work on the museum with her ideas and advice. The conservation work was carried out by Marjanca Jeglič, and Mateja Likozar, the photo archive manager, prepared the necessary photographs. Additional help came from Andrej Dular of the Slovene Ethnographic Museum, Mateja Kos of the Slovene National Museum, Mojca Šifrer-Bulovec of the Škofja Loka Museum, and Brane Dežman, who provided the graphic design for the signs and this brochure.

My cooperation with skilled craftsmen from Podblica was fruitful. The wood that my husband gathered from the local forest was processed by the craftsmen Vili Šturm, Janez Šturm, and Jože Bertoncelj. They also took time to assemble the missing part of the ironing device based on old plans – a box (Slovenian kišta) measuring 5 m long, 90 cm wide, and 87 cm high that holds 5 tons of stones from the Sava River. The device was thus made ready for its job: ironing.

The contribution of Milka Bertoncelj is also important. Her story about the production of linen recalls a trade that was very common in this part of Slovenia because, for a long time, it represented the only way to obtain fabric for everyday use, and at the same time was an additional source of income.

My thanks goes to all of them.

If you would ever like to visit the museum, you are warmly invited to do so.

THE PIRC DYE-WORKS

and how it operated

The beginnings of the dye-works, later known as the Pirc Dye-Works, go back to the early 18th century. The dye-works developed and successfully established itself in the following century. In the mid-19th century it ranked as one of Slovenia's medium-sized manufacturing facilities. Mainly linen and cotton were dyed at the dye-works. Orders came from Vienna, Trieste, Prague, Linz, Klagenfurt, and other cities of Austria-Hungary. A considerable number of convents throughout the monarchy were also supplied with products from the works dyed black or printed blue. Cotton was dyed blue or red and was woven into beautiful checkered patterns with white cotton.

Wool products were also dyed: socks, sweaters, dresses and shawls that were brought by local farmers. The dye-works had red, blue, dark indigo, green, and black dyes, which were imported from Germany. Upon request, material was also hand-printed.

HOW THE DYE-WORKS OPERATED

Material brought by customers to be dyed was taken to the workroom (Slovenian virštat). This room had a large chimney 10 meters in diameter. Furnaces were built around it (Picture 1). The furnaces had copper kettles used for boiling dye that had been pulverized beforehand using iron balls of various sizes. The dye was then poured into a wooden tub (Slovenian kipa) in the floor with pulley attached to the ceiling above (Picture 2). A wooden or iron frame (Slovenian ram) was suspended from the pulley. The material was pinned to these frames, lowered into the dye using the pulleys, and pulled out after the dyeing was finished. This procedure would last a few hours.

After the dyeing was finished, the material was taken off of the frames, placed onto a two-wheeled wooden tipcart (Slovenian kimpež), and taken to the Kokra or the Sava River, where it was rinsed in the running water.

The material was dried in the area behind the house, or inside the house in the attic on a rack (Slovenian grablje). In winter, it was dried in a closed, well-heated part of the attic called the dry room (Slovenian trokenštube).

The dried material was then brought to the mangle room to be ironed by the mangle – an oak box 5 meters long, 107 centimeters wide, and 90 centimeters deep filled with stones from the Sava River (Slovenian savske kugle). First, the material was dampened and pressed, then rolled up around large dowels and placed under the mangle. So that the weight of the box would flatten and straighten the material, the box was moved back and forth across the cylinders with the help of a mechanical drive (a special winch) that was powered either by animals or people.

The ironed material was arranged by yardage or piece and returned to the customer. Upon receiving the fabric, the customer would return the split tally (Slovenian roš) received when the fabric was turned over to the dyer.

When a customer brought fabric to the dyer, he would fasten a split tally or a token to every piece of fabric that was handed over to him. These tallies were brass, iron, or tin plates of various shapes (round, triangular, square, or diamond) with the imprinted initials of the dye-works owner and a serial number. The tallies were always made in pairs. One was given to the customers when they brought their fabric, and the other one was kept by the dyer, who fastened it to the fabric and then drew it in a notebook and wrote down the customer's name and order for dyeing or printing. The tally also served as a guarantee. If a customer lost the tally, the dyer would still return the fabric; however, the dyer would keep the tally that was fastened to the customer's fabric in a safe place. He would wrap it in a piece of paper, write down the customer's name and address on the inside, as well as the type of work that was done, the amount paid, and the date. On the outside, he would carefully draw the tally, together with the initials and the serial number. If a third person happened to find the lost tally and came to claim the fabric, the dyer could prove that the fabric had been given to the real owner by showing the tally that he kept.

THE OWNERS OF THE DYE-WORKS

ANDREJ PAVEL MARENIK (1681–1756)

Andrej Pavel Marenik was the founder of the dye-works. He came to Kranj from Škofja Loka, bought a house on Roženvenec (‘Rosary') Slope next to the river, and began his trade.

LOVRENC PIRC (1698–1783)

Lovrenc Pirc married Andrej Pavel's daughter Marija Ana in 1754. He was an expert dyer from Škofja Loka. When they married, he brought 400 guldens to the household and the father-in-law entrusted the young couple with the management of the dye-works. Lovrenc bought more land around the house and expanded the property. The house became the home of the Pirc family, known locally as Lovrenc's Place (Pr' Lorênčk). He also produced an ointment known as "Lovrenc's Salve" that helped heal wounds.

ANDREJ PIRC (1755–1808)

Andrej was the son of Lovrenc and Marija Ana. He modernized the ironing of fabric. He set up a press for this purpose in 1797.

SIMON PIRC (1788–1851)

Simon was Andrej's son and continued his father's work. In 1809, he added a mangle to the press. He increased the size of the manufacturing facility and modernized it. The inventory that was taken almost a year after he died was proof that the dye-works was doing very good business at the time.

AGNES PIRC (1811–1865)

Agnes was Simon's daughter, who inherited the dye-works as the oldest child and successfully managed it until her death. She died unmarried and without heirs.

MATEJ PIRC (1824–1891)

Matej was Agnes' brother, who was educated as a mining engineer. After his sister's death he quit his managerial position at the mine in Toplice near Hotavlje, returned home to Kranj, and took over the management of the family dye-works. He was not interested merely in the development of his dye-works, but also interested in the preservation of linen manufacturing. Around 150 farmers worked for him as weavers in surrounding villages such as Besnica and Bitnje. At his home he dyed and pressed the linen that he bought from the farmers, and then he sold it to various parts of Austria-Hungary through his store, which he opened in 1864.

METOD PIRC (1867–1891)

Matej's youngest son Metod began learning the trade at an early age because his father appointed him the heir to the dye-works. He had the appropriate education, he was interested in and enjoyed the goings on at the dye-works, and he started planning its modernization. Unfortunately, both he and his father Matej died in 1891.

CIRIL PIRC (1865–1941)

Metod's older brother Ciril therefore had to abandon his study of law in Vienna, return home, and take over the trade. Rapid industrial development, including in the textile industry, strengthened his conviction that the age of textile manufacturing was coming to an end. He gradually phased out the work at his family dye-works, but as the mayor of Kranj (1921–1935) he tried his best to attract the textile industry to his town. His plan succeeded with the support of like-minded individuals and a group of ambitious young Slovene entrepreneurs. Kranj developed into the second most important center of the textile industry in Slovenia.

FROM FLAX TO LINEN

Linen manufacturing was a very important activity for the farmers as well as town craftsmen in the area of Kranj and in the Dominion of Škofja Loka. Linen manufacturing reached its peak in the 18th century. At that time, local farmers were weaving linen for Matej Pirc, among others. Linen manufacturing slowly disappeared at the end of the 19th century due to the increasing importance of industrially produced cotton fabrics on the market. The decline of linen manufacturing brought also led to the collapse of the dyeing industry.

You can learn more about the history of linen manufacturing and production procedures at the permanent exhibition on linen manufacturing at the Škofja Loka Museum.

Milka Bertoncelj (residing at Podblica 14) described how flax was cultivated and harvested in the village of Podblica and the surrounding area in the following narrative, which was written down in March 2006.

In the spring, flax was sown very densely (it was said that there had to be nine seeds per inch) so that the small shoots that sprang up would be as thin as possible. It matured in August.

At that time, the flax was pulled by hand. It was gathered into fist-sized sheaves and laid down crosswise. The bolls were removed from the stems with ripples (Picture 1). The flax was rippled and laid down crosswise while still in sheaves.

Then, for about three weeks, the seedless stems were left in a meadow, spread out as far apart from each other as possible, to allow the outer layer to ret in the rain and the sun. Then it was gathered into sheaves once again. The breaking and separation of the fiber followed. First, the sheaves were dried in a drying room (Picture 2), which contained a furnace, a chimney (Slovenian rajfenk), and a pit. The furnace was connected to the pit with a long underground tunnel from which the chimney rose. The pit was two to three meters deep, and near the middle it had a wooden lattice where the sheaves of flax were placed upright, covered with sackcloth, and left to dry in the warm air that came from the furnace through the tunnel. In some places, the sheaves were spread out across a drying rack that was placed on top of the pit (Picture 3). The fire was made only with beech wood, which does not produce sparks, otherwise the flax could have caught fire and burned.

The dry flax was broken with a brake (Picture 4). Usually a few workers broke the flax at the same time. The brakes were supported by a central beam on one end and poles on the other (Picture 5). The blunt blade of the brake crushed the retted stems so that the brittle outer layer fell off and all that was left was the fibers.

The thickest fibers were removed immediately (Picture 6). They were later beaten with a rod, and woven into burlap (Slovenian tule) – the lowest quality linen. This was used to make sheets for carrying hay or leaves.

The remaining fibers were gathered into fist-sized hanks (Slovenian šop), and each was tied into a knot on top. Thirty-two such hanks were gathered into a bundle (Slovenian pušl; Picture 7). The bundles of fibers waited for further processing.

The preparations for spinning began in winter. The bundle was untied and each hank was combed and smoothed with a special hackle (Picture 8). In this way, linen of two different qualities was obtained.

The thicker fibers (the tow) remained on the hackle and were gathered into a bunch (Slovenian kodelja) ready for spinning. They were used to spin thicker yarn for tow cloth (Slovenian hodník), which was used for sheets, work clothes, and so on.

The thinnest fiber (the line fiber) remained in the hand during hackling; these fibers were bound into a strick (Slovenian prevêsm) and were used to produce the best thread for fine linen, which was used for bedding, underclothes, and clothing for special occasions.

The spinning was done on a spinning wheel (Picture 9). The yarn was spun on a spindle (Picture 10), and then coiled into a skein on a reel. The skeins were washed and dried, put back on the reel, and the yarn was wound into a ball. These balls were then used for weaving.

Woven linen was grayish, so it was bleached by soaking and exposure to the sun, and then it was laundered in lye that had been leached from beech ashes.

CIRIL PIRC (17 February 1865 – 29 May 1941)

After finishing secondary school, Ciril Pirc enrolled in law school in Vienna. He was unable to take his final exams due to the sudden deaths of his father Matej and brother Metod. He had to discontinue his studies and take over his father's trade and shop.

He became active in public life fairly early on, influenced by the notary Viktor Globočnik, first as an active member of local patriotic groups (e.g., the National Reading Society, the Upper Carniolan Sokol athletic society, the Slovene Hiking Society, the Music School, and the Fire Brigade), and then as a member of the provincial assembly, when he supported the opening of the Kranj–Tržič railroad, the construction of a new bridge across the Sava River, and especially the construction of a water system for Kranj and its surroundings.

He was made an honorary citizen by the municipal committee of Kranj and he was elected mayor of Kranj the same year. He remained mayor until 1935. As mayor, he strove to improve the town's economy (by developing the textile industry and founding a textile school) and its infrastructure (e.g., the sewage system, paved streets, improved streetlights, etc.).

From 1931 to 1935, Pirc was a member of the Provincial Council. His dedicated work earned him numerous decorations, including the Order of St. Sava (3rd, 4th, and 5th class) and the Order of the Yugoslav Crown (2nd and 4th class).

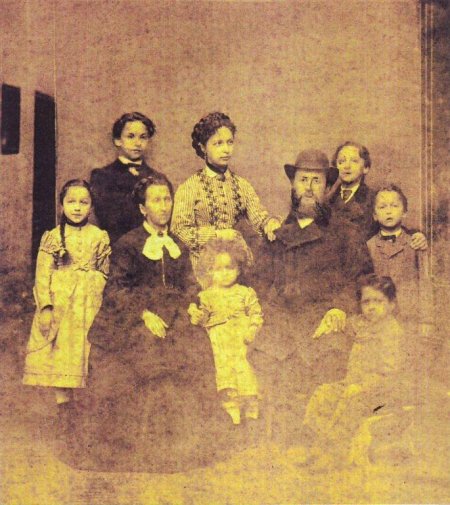

Matej Pirc and his family in Kranj (ca. 1873)

Vodopičeva 11

4000 Kranj, Slovenia

Tel. +386 4 202 7011

+386 40 791 196

Kranj, September 2006

English translation: DEKS d.o.o.